The Art of the Ukraine: Ilya Repin

31.5.2022 by Oleksandra Sakorska

Blog series on Ukraine’s artistic tradition

At the beginning of April 2022, the Liebermann-Villa was able to create a position in our team for a new assistant curator, Oleksandra Sakorska, who previously worked for ten years at the Khanenko National Museum of Art in Kyiv. The position was made possible by the UKRAINE-funding programme of the Ernst von Siemens Kunststiftung.

In this new blog series Oleksandra Sakorska will introduce us to some of the most important and most interesting names in Ukrainian art history, from the late nineteenth-century onwards. The series explores artists born within the borders of today’s Ukraine, exploring their connections to Ukrainian history, music, literature and society.

Many of these names were repressed during the Soviet period and remain largely unknown outside the Ukraine today. In this series, we would like to consider how Ukrainian cultural identity was changed by the establishment of the Soviet Union, and to link this to how cultural discourses and identity may be changing again through the catastrophe of the current war.

We look forward to learning more about Ukraine’s fascinating artistic tradition!

Ilya Repin

Ilya Repin (1844, Chuguev, Kharkiv Province – 1930, Kuokkala, Finland- today Repino, Russia) was born to a Cossak family in the town of Chuguev, today in the north east Ukraine. His native town, to the east of Kharkiv city, is the heart of the historical region known as “Sloboda Ukraine”. He started making art by painting and ornamenting traditional Ukrainian Easter eggs (pysanky), a craft which was, and still is, very popular in Ukraine. Repin’s first art teacher was a local Ukrainian icon painter. Further important early influences were the traditional Ukrainian epics (Dumas) and the poetry of Taras Shevchenko (1814–1861) – a popular Ukrainian writer, artist and political figure, a folklorist and ethnographer whose portrait Repin later painted.

Fig. 1 Ilya Repin, Portrait of Taras Shevchenko, 1888, National Museum Taras Shevchenko, Kyiv

Studies in St Petersburg and Paris

Repin continued his artistic studies at the Academy of Art in St Petersburg. Already at this time he was exploring specifically Ukrainian themes in his work. From 1873 to 1876 Repin toured Italy and settled in Paris where he got to know some of the works of the French “realist” Courbet and was also exposed to the French impressionists. Manet in particular impressed Repin, inspiring him to imitate the French artist’s style. Even in Paris, however, Repin could not completely forget Ukraine: two portraits on Ukrainian themes date from this period, “The Ukrainian Girl“ and “A Ukrainian Girl by a Wicker Fence“.

Fig. 2 Ilya Repin, The Ukrainian Girl, 1875, Pushkin Museum, Moscow

Fig. 3 Ilya Repin, A Ukrainian Girl by a Wicker Fence, 1876, Latvian National Museum of Art, Riga

The return to his homeland

After his stay in Paris, Repin returned to his homeland in 1876. This year, 1876–77, was one of the happiest in the artist’s life: his only son was born, and Repin himself experienced a creative rebirth. He enthusiastically absorbed the life and habits of the Ukrainian provinces, as he once exclaimed, “How charming! What a Delight! […] Only Ukrainian and Parisian girls really know how to dress tastefully!”. The products of this affection and deep interest can be seen for example in the painting “The Evening Party“, completed in 1881, which depicts a group of Ukrainian folk dancers.

Fig. 4 Ilya Repin, The Evening Party, 1881, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

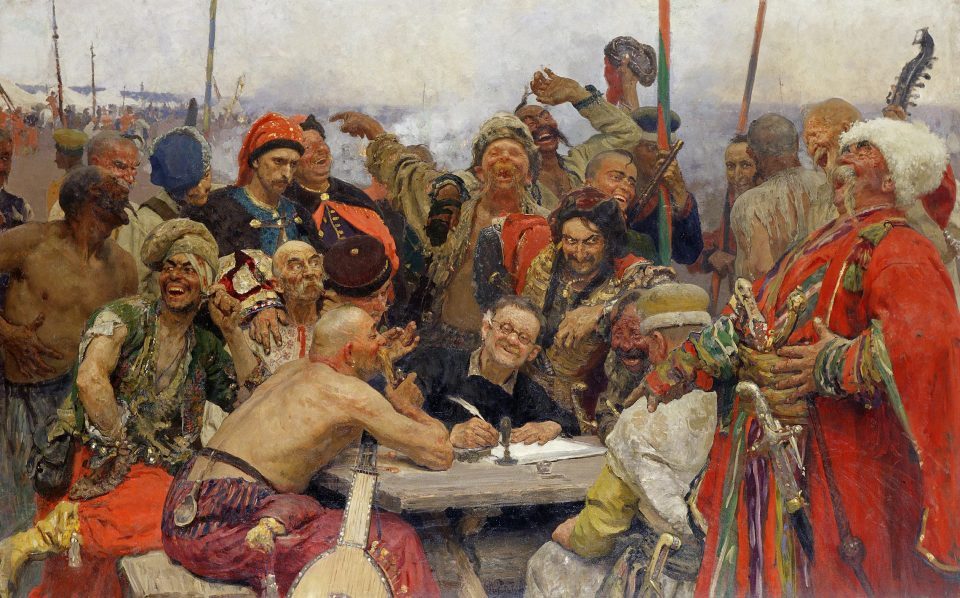

This endless interest in Ukrainian history and culture inspired ambitious projects such as the large-scale history painting “Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks“ started in 1878, and which was only finished some thirteen years later in 1891. In this detailed, monumental work the artist was also inspired by the publications of Ukrainian historian Mykola Kostomarov (1814–1885), who in his work looked to Voltaire and the latter’ claim that “Ukraine has always aspired to be free.” This painting was awarded by a golden medal at the International exhibitions in Munich and Budapest, in 1895.

Fig. 5 Ilya Repin, Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks, 1891, Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg

Fig. 6 Ilya Repin, Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks, version II, 1893, Kharkov Art Museum

Being a member of The Wanderers “Peredvizhniki” (an artists’ cooperative in protest of academic restrictions), Repin travelled through Ukraine in 1880, accompanied by his pupil Valentin Serov (1865–1911), preparing drawings for his sketch book ‘Little Russian Types’. The sketches he later used for the painting “Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks“. During their trip Repin and Serov studied weaponry and costumes, portrayed the locals and painted the countryside. Repin also spent time at Kachanivka Palace (Chernihiv Province), then the residency of the famous Ukrainian collector V.V.Tarnovskyi (1837–1899). Among other visitors to Tarnovskyi during this period were Nikolai Gogol, Taras Shevchenko, Mikhail Vrubel and Mikhail Glinka.

Fig. 7 Ilya Repin, Khata, 1880, National Museum “Kyiv Picture Gallery”

Fig. 8 Ilya Repin, On the Trail, 1881, Samara Regional Art Museum

A large-scale masterpiece by Repin is the painting “They did not Expect Him“ – a work with a deep understanding of psychology. Once again, it also shows specifically Ukrainian motifs, such as a portrait of Taras Shevchenko.

Fig. 9 Ilya Repin, They did not Expect Him, 1884, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

The move to Finland

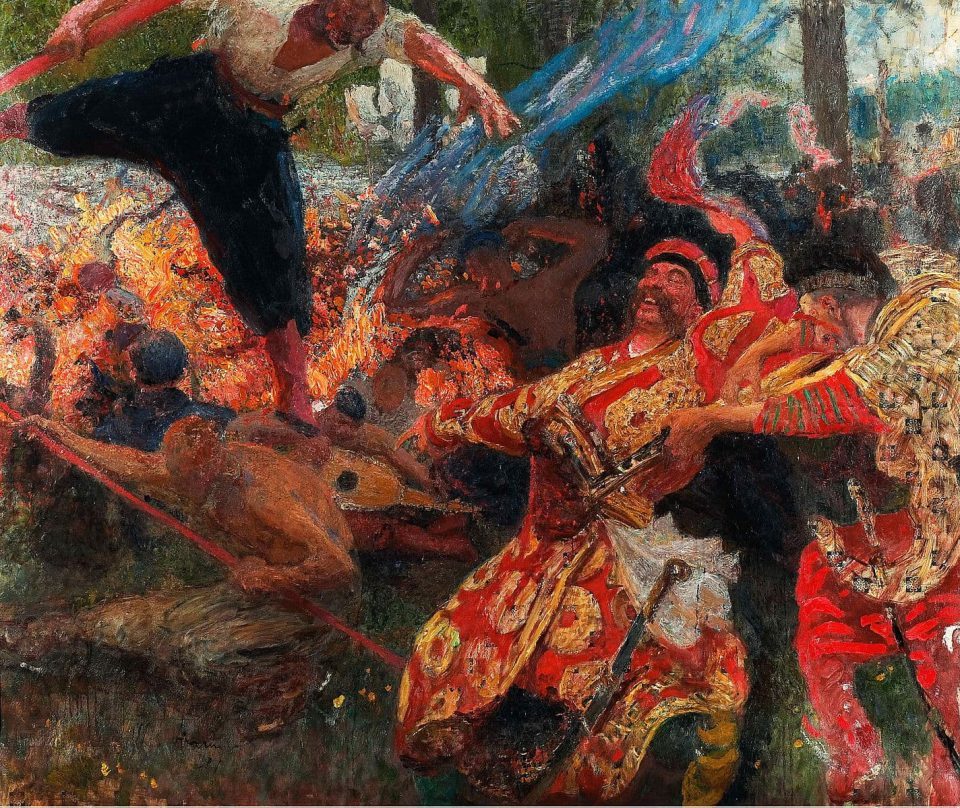

At the start of the Twentieth Century Repin grew increasingly uncomfortable with growing Russian nationalism in Ukraine. After Finland became independent in 1917 he moved to the country, staying there until his death. Though the Soviets invited him to return to the USSR, he refused their requests. In 1930 Repin passed away and was buried in the grounds of his family home in Kuokkala. On the artist’s easel was found an unfinished painting “The Hopak“, and a shabby copy the poetry collection “Kobzar” by Taras Shevchenko. Today Repin’s home is a museum dedicated to the artist, located in the village of Repino – formerly Kuokkala, Finland – renamed in 1948 after its most famous inhabitant.

Fig. 10 Ilya Repin, Gopak, 1927, Private collection

Connection to Max Liebermann

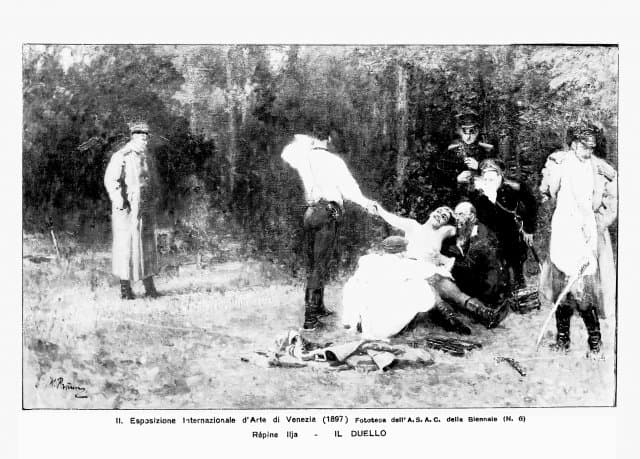

Both Liebermann and Repin were in the Patronage Committee of the Second International Art Exhibition in Venice [Biennale of Venice] in 1897. The Russian hall at the 1897 Biennale was an important early showcase for the Russian art in Italy. According to the jury of the competition, Repin’s painting “Duel“ was the work that gave rise to the loudest criticisms and the most diverse opinions.

Fig. 11 Ilya Repin, Duel, 1896, private collection, USA

(from the Magazine L’Illustrazione italiana, XXIV, 43, 1897, S. 265)

As critic Achille de Carlo wrote of the show in 1897: “The artistic temperament of Russians is perhaps the most delicate and perfect; because the southern color and fervor are complemented by the subtlety of fantasy, the neutral gradations of the northern people, the great naivety of the young nation, and the ability to assimilate, choosing the best from each school, without following it or slavishly imitating it. True, there is still something barbaric in them; they are a bit pompous, they enjoy all those effects and contrasts as children or primitive people do; beside thoughts and deep ideas, one will find naivety bordering on conventionality, where if not a European, then a Cossack will definitely show up.”

Fig. 12 Monument to Ilya Repin, 1984, Kyiv. Photo 2020

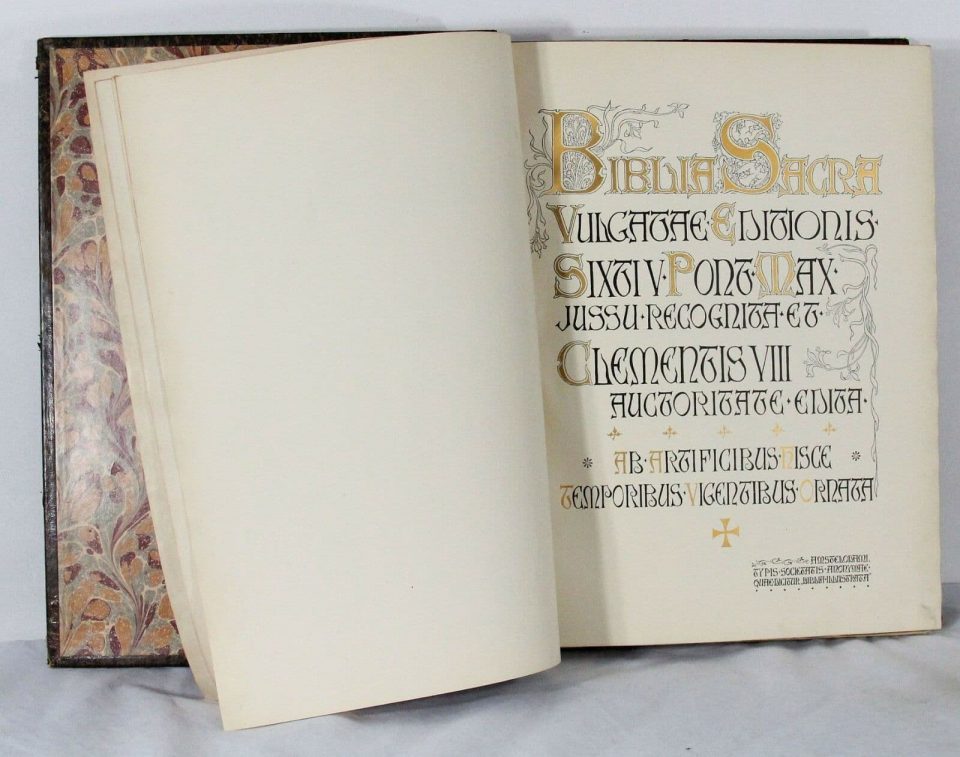

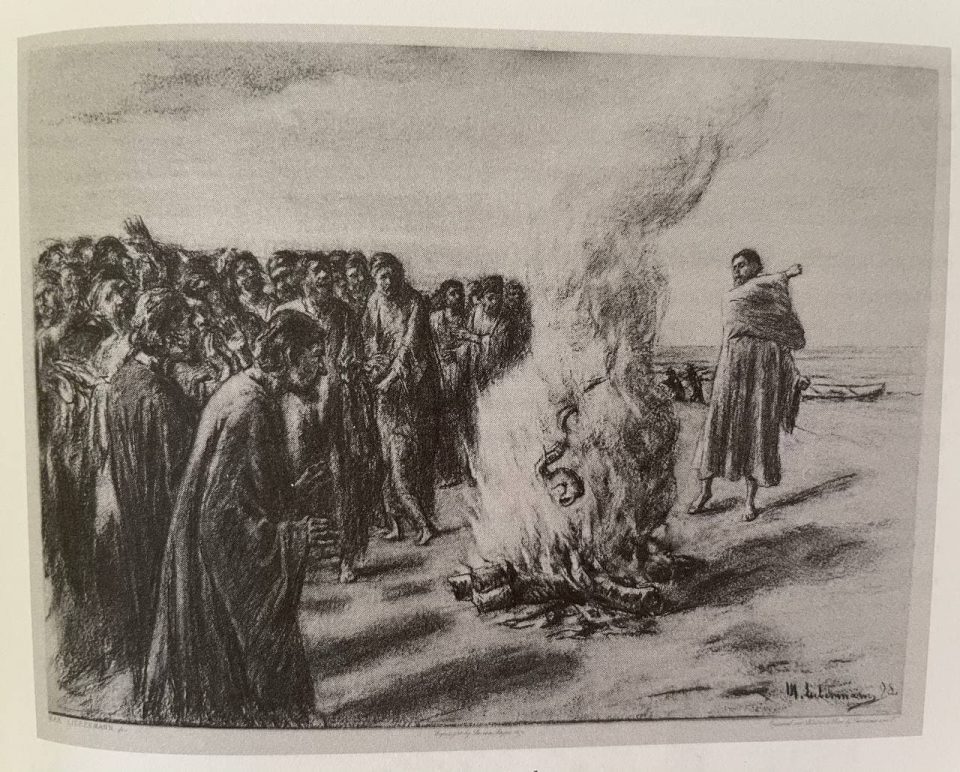

Another interesting connection emerges when studying the lives of the two artists Liebermann and Repin. Both were involved in the creation of drawings for De Geïllustreerde Bijbel (The Illustrated Bible, 1900) – a Dutch Bible edition, initiated by the Illustrated Bible Society, containing 100 plates in heliogravure by 27 artists from all over the world and decorated by the British painter and illustrator Walter Crane.

Fig. 13 Title page of Walter Crane, Omslag van de Geïllustreerde Bijbel. Van Holkema & warendorf, Amsterdam 1900

Fig. 14 Based on a drawing by Max Liebermann: Paul and the Adder (Acts XXVIII.5.) from Crane (1900), Vol. 3, ill. 89