Grete Ring. Dealing in Modernism

Find out more about the art dealer and art historian Grete Ring with our audio guide.

Please find the English wall texts below.

Introduction

Welcome to our exhibition Grete Ring. Dealing in Modernism. From Cézanne and Renoir to Liebermann and Kokoschka. Join us on the trail of Grete Ring!

"Living German Art"

Between autumn 1932 and spring 1933 Grete Ring organised the three-part exhibition series “Living German Art”. This series marked the end of an ere of innovation and creativity in Berlin – one of the last presentations of modern art before the National Socialists came to power.

van Gogh-Fakes

Two of the Wacker forgeries can be seen here in this room: “The Sower” and “The Reaper in the Cornfield.” They were probably painted by Otto Wacker’s brother Leonhard.

Grete Ring and the Liebermann family

Born Margarete Ottilie Ida Ring, Grete Ring had close relation to the Liebermann family. Her mother, Margarete Marckwald, was the younger sister of Martha Liebermann.

A gem in Sacrow

After leaving Germany, Grete Ring was completely cut off from Berlin. Later she heard from Marianne Feilchenfeldt how her house in Sacrow – including her designer furniture – had been rented out to a local fisherman.

Grete Ring in England

Grete Ring quickly made new contacts in England. Her first exhibition at Paul Cassirer Limited in July 1939 – watercolours by Paul Cézanne – was a success.

Grete Ring and Max J. Friedländer

Grete Ring and Max J. Friedländer shared an close friendship – this is proved by the many letters they sent each other over the years. They knew each other from Berlin – Friedländer was a museum director and expert in the field of Old German and Old Netherlandish painting.

Grete Ring's drawing collection

Grete Ring was able to take her private collection of drawings with her in exile to England. Her collection mainly comprised works by 19th and early 20th century French and German artists, including Ingres, Corot, Manet, Millet, Degas, Delacroix, Friedrich and Schinkel.

Grete Ring and Katerina Wilczynski

The illustrator Katerina Wilczynski is almost forgotten today. Wilczynski and Ring met in 1920s Berlin. At that time, Wilczynski was a popular illustrator – in the cultural magazine Der Querschnitt, for example, for a time her drawings were printed in almost every issue.

Production

Texts, editing: Lucy Wasensteiner, Viktoria Krieger

Production: Studio Brod, Berlin

English Wall Texts

Grete Ring. Dealing in Modernism.

From Cézanne and Renoir to Liebermann and Kokoschka

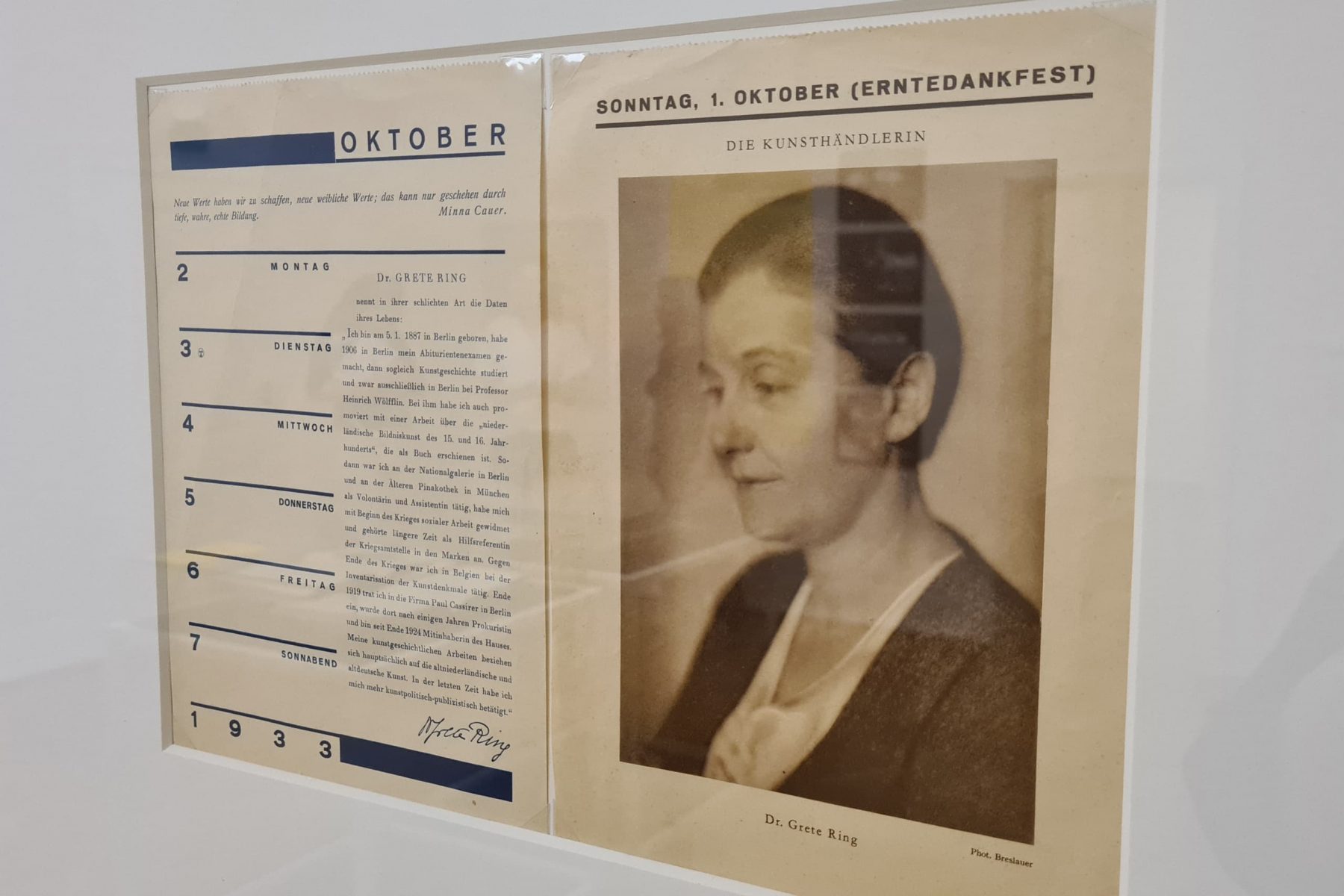

Grete Ring (1887-1952) was a brilliant art historian and renowned art dealer. In 1912 she was one of the first women to be awarded a doctorate in art history; from 1918 she worked for the famous Kunstsalon Cassirer dealership in Berlin. Ring and her business partner Walter Feilchenfeldt senior took over the art dealership in 1926 after the death of the founder Paul Cassirer. Ring was in close contact with the most important artists and collectors of the time – including Oskar Kokoschka – and built up her own collection, mainly of drawings by 19th-century German artists and French modernists. Ring was also closely connected with the Liebermann family. Her mother was a sister of Martha Liebermann, the wife of Max Liebermann.

Why is Grete Ring’s name not more widely known today? Certainly her status as a woman in a male dominated profession played a role. Also significant however – the many interruptions to her personal and professional life. In 1938 she had to leave her hometown of Berlin because of the anti-Semitic policies of the National Socialists. She ventured a new start in London and founded a new branch of the Cassirer company there in 1939.

This exhibition is a first attempt to compile surviving sources on Grete Ring and to reconstruct her life and career. Particularly important here is Ring’s correpondence with the photographer Marianne Breslauer – Walter Feilchenfeldt’s wife – and Breslauer’s later memoirs. Using these texts, together with other archival material, photographic material, artworks, press cuttings and publications, this exhibition attempts to present something of Grete Ring and her remarkable achievements. The exhibition also includes original artworks from Ring’s private collection – including drawings and sketches by Paul Cézanne, Pierre Auguste Renoir, Adolph Menzel and Caspar David Friedrich. After Grete Ring’s death, these drawings were bequeathed to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. For our exhibition, these artworks have travelled back to Berlin for the first time.

Thanks

This exhibition is generously supported by our lenders, including the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz (Alte Nationalgalerie and Kunstbibliothek) and the Georg Kolbe Museum in Berlin – our special thanks to them all. We would like to thank the “Hauptstadtkulturfonds” for their financial support of this exhibition. We would also like to thank the patrons of the exhibition, Dr Felix Klein, Federal Government Commissioner for Jewish Life in Germany and the Fight against Anti-Semitism, and Paul Smith, Director of the British Council in Germany.

We would in particular like to thank Rahel and Konrad Feilchenfeldt for their great commitment to this project and their unwavering support.

Paul Cassirer and the Kunstsalon Cassirer

In the years after the First World War, Paul Cassirer established himself as the leading dealer of modern art in Berlin. The pioneering work of his “Kunstsalon Cassirer” becomes clear with a look at his exhibition program: Else Lasker-Schüler, Wilhelm Lehmbruck and Max Slevogt (1920), Edvard Munch and Paul Cézanne and Georg Kolbe (1921), Oskar Kokoschka, Marc Chagall and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1923), Max Beckmann and Ferdinand Hodler (1924). Paul Cassirer is also considered Max Liebermann’s most important art dealer. The dealership’s archives – which do not survive in full – mention around 2,300 Liebermann works. All the Liebermann paintings shown in this room passed at some point through the Kunstsalon Cassirer.

Grete Ring joined the Cassirer firm in around 1918 on the recommendation of Max J. Friedländer, then-director of the Berlin Kupferstichkabinett (Museum of Graphic Art). Years of successful collaboration between Ring, Cassirer, and their business partner Walter Feilchenfeldt followed. On 7 January 1926 however, tragedy struck. When Paul Cassirer’s wife, the actress Tilla Durieux, served him with divorce papers, Cassirer shot himself in his lawyer’s office. The dramatic death of the 54-year-old made headlines across Europe. Max Liebermann, Harry Graf Kessler and the art dealer Justin Thannhauser spoke at Cassirer funeral. Grete Ring and Walter Feilchenfeldt then took over the Kunstsalon Cassirer.

Dealing in Modernism

Grete Ring had many talents. Her doctoral thesis “Dutch Portrait Painting in the 15th and 16th Centuries” was supervised by the legendary Munich professor Heinrich Wölfflin; during her studies she started publishing her first journal articles . After working at the Pinakothek der Moderne Museum of Modern Art in Munich and the National Gallery in Berlin, following the outbreak of the First World War she took up a position at the Kunstsalon Cassirer. According to the art historian Max J. Friedläner, Ring was the “art-historical heart” of the Cassirer business. She built up a broad network and was in contact with the most important figures of modern art, including Emil Nolde, Erich Heckel, James Ensor, Max Slevogt and Else Lasker-Schüler. She was also a friend to many of them, including the illustrator Katerina Wilczynski or the painter Oskar Kokoschka, who portrayed Ring in 1923.

With Paul Cassirer and Walter Feilchenfeldt, and from 1926 with Feilchenfeldt alone, Grete Ring organised numerous exhibitions and auctions for the Kunstsalon Cassirer. Among the most important auctions of these years were those of the collections of Oscar Huldschinsky (1928), Joseph Spiridon (1929) and Albert Figdor (1930). Among her best-known exhibitions was the three-part series “Living German Art,” which ran from December 1932 to spring 1933. This series, organised together with the art dealer Alfred Flechtheim, sent a clear signal against the cultural policies of the National Socialists, with works by names later defamed as “degenerate”: Paul Klee, Willi Baumeister, Renée Sintenis, Erich Heckel and Oskar Kokoschka. Georg Kolbe’s bronze Sitting Man – now owned by the Georg Kolbe Museum in Berlin – was part of the second “Living German Art” exhibition in January 1933.

Grete Ring also built up her own art collection – mainly comprising French and German nineteenth-century drawings. A selection of the drawings acquired during her Berlin years are on display in this room.

A Personality on the Art Market

Grete Ring did not only write for auction and exhibition catalogues published by the Kunstsalon Cassirer. Her essays appeared regularly in such journals as Kunst und Künstler, Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst, Das Kunstblatt, Der Kunstwanderer and Die Weltkunst. Grete Ring herself became a well-known face of the Berlin art market. In 1928, she even appeared as a caricature in the magazine Kunst und Künstler. The drawing shows Ring next to Walter Feilchenfeldt and Hugo Helbing at their auction of the Huldschinsky Collection.

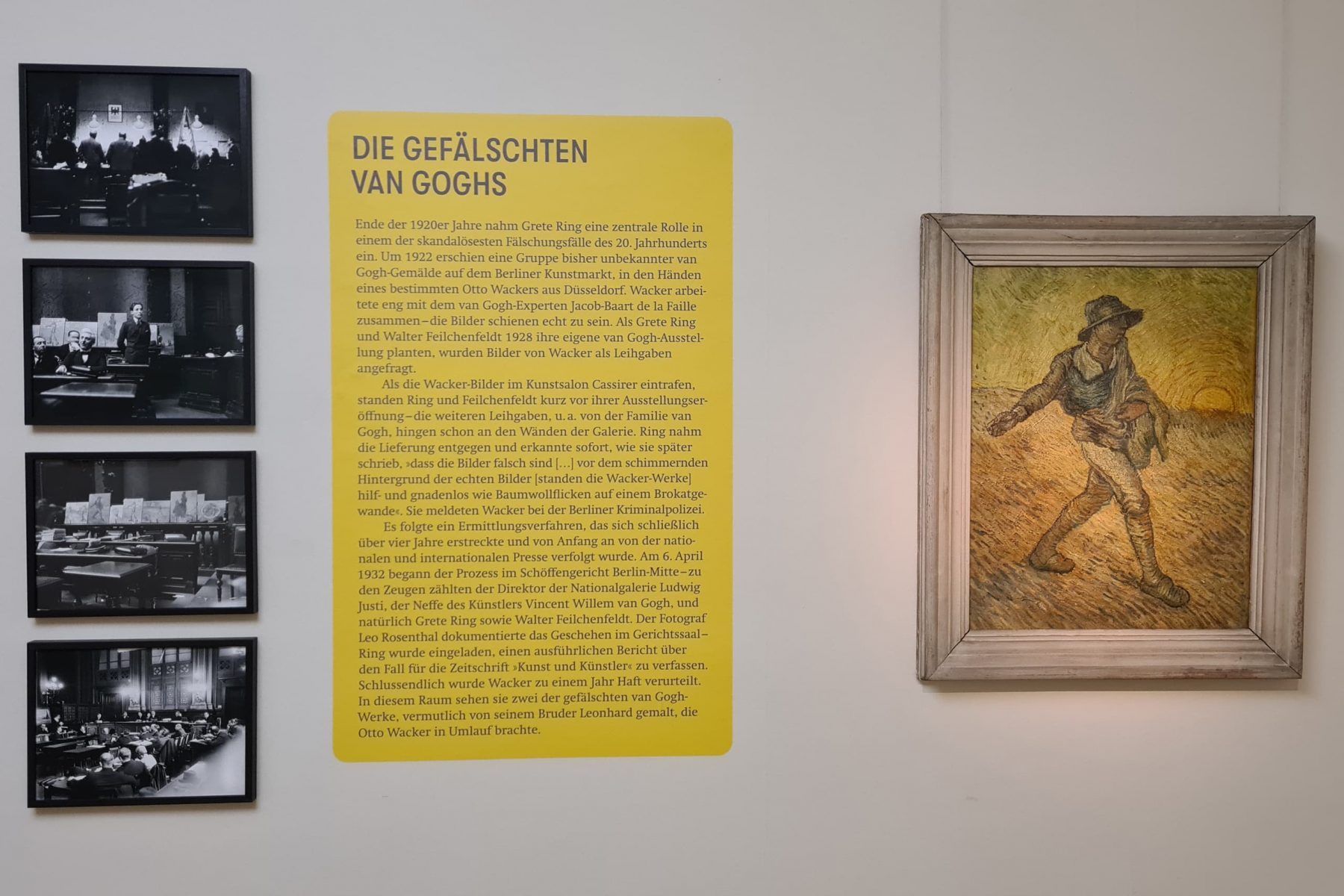

The Fake Van Goghs

In the late 1920s Grete Ring played a central role in one of the century’s most scandalous art forgery cases. Around 1922, a group of previously unknown van Gogh paintings appeared on the Berlin art market, in the hands of an dealer named Otto Wacker of Düsseldorf. Wacker worked closely with the van Gogh expert Jacob-Baart de la Faille – the paintings appeared to be genuine. When Grete Ring and Walter Feilchenfeldt came to hold their own van Gogh exhibition in 1928, paintings in Wacker’s possession were requested as loans.

When the Wacker loans arrived at the Kunstsalon Cassirer, Ring and Feilchenfeldt were about to open their exhibition – the other loans, including those from the van Gogh family, had already been hung. Ring immediately realised, as she later wrote, “that the paintings were wrong […] against the shimmering background of the real paintings [the Wacker works] stood helplessly and mercilessly like cotton patches on a brocade robe”. They reported Wacker to the police.

This was followed by an investigation that eventually stretched over four years and which was followed closely by the national and international press. The trial began on 6 April 1932 at the Assessor’s Court of Central Berlin – witnesses included the director of the Berlin National Gallery Ludwig Justi, the nephew of the artist Vincent Willem van Gogh, and of course Grete Ring and Walter Feilchenfeldt. The photographer Leo Rosenthal documented the events in the courtroom. Ring was invited to write a detailed report on the case for the magazine Kunst und Künstler. In the end Wacker was sentenced to one year in prison.

In this room you can see two of Wacker’s forged van Gogh works.

Childhood and Family

Grete Ring was related to Max Liebermann’s family. Her mother Margarethe Ottilie Marckwald was the younger sister of Max Liebermann’s wife Martha. A portrait of Ring’s mother from 1889 can be seen in this room. Ring’s father, Victor Julius Ring, was a successful lawyer, judiciary council member and later vice-president of the Berlin Supreme Court. On Grete Ring’s birth certificate, the religion of her parents is noted: Victor Ring “Protestant”, Margarethe Marckwald “Mosaisch”, meaning Jewish mosaic.

Grete Ring grew up as an only child – first in a house at 73a Potsdamer Strasse, later at 46 Schöneberger Ufer. Her parents were well-known in cultural circles – around the turn of the century they commissioned a portrait of their daughter by the Secession artist Dora Hitz. Grete Ring was close friends with her cousin Käthe Liebermann – the only daughter of Max and Martha Liebermann. Ring’s friend Marianne Feilchenfeldt later wrote that “[Ring] and her cousin Käthe […] were obviously extraordinarily pretty girls, and Grete insisted on telling me that she had never slept a night, going from one ball to another”. Until her death, Grete Ring kept a group of photographs that she and Käthe had taken as young women, presumably during holidays in southern Germany or Switzerland. When Käthe gave birth to her own daughter, Maria, in 1917, Grete Ring was her godmother.

A Modern Woman

Grete Ring was a thoroughly modern woman: she had a career, was extremely successful, and travelled all over Europe on behalf of the Kunstsalon Cassirer dealership. Her friends nicknamed her “witch” – a title she also used for herself – because she so often travelled by plane, or as she termed it, by “broomstick”. Grete Ring remained unmarried and enjoyed her freedom, as Marianne Feilchenfeldt later wrote “she was not at all suited to something as conventional as a marriage”.

In 1927 Ring acquired a plot of land in the village of Sakrow near Potsdam. With her poodle Strohmian she sought a temporary escape from the city. She commissioned her architect friend Wilhelm Büning to design her a one-storey summer house – with its flat roof and sun deck Büning created an iconic, modern building for this modern art historian. Ring furnished her summer house with simple contemporary furniture, including pieces by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and custom-made black and yellow shelving units. Large glazed doors opened up the view into the garden. The “witch’s house” – as she herself called it – became a popular meeting place for Ring and her friends.

Exile in England

The Nazi takeover in 1933 was a crossroads for many – including Grete Ring. In spring of 1933, Walter Feilchenfeldt – who also came from a Jewish family – left Germany to work from the Amsterdam branch of the Kunstsalon Cassirer. Grete Ring initially remained in Berlin. In 1935, when the “Reich Citizenship Law” was passed in Germany to distinguish “Aryans” from “non-Aryans”, preparations began to move the business abroad. Ring, Feilchenfeldt and their Dutch colleague Helmuth Lütjens travelled to England to explore the possibility of a London dealership. In May 1938 Ring left Berlin for the British capital.

Within a few months, Ring was able to establish a new existence in London. She founded a British branch of the Berlin firm – Paul Cassirer Ltd – with business premises at 11 Cleveland Row, St James. She opened the new gallery in July 1939 with an exhibition of Cézanne watercolours. The show received a good deal of interest in the British press.

On the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939, Walter Feilchenfeldt found himself in Switzerland. It now became impossible for the Feilchenfeldt family to join Grete Ring in England. Ring was left to run the London business alone.

England at War

In September 1940, the business premises on Cleveland Row were bombed. Ring had to leave London and moved to the suburbs. Her letters show that she initially lived at “Square Cottage, Hazel Lane, Richmond” with her friends and fellow-émigrés, the art dealer Arthur Kauffmann, his doctor wife Tamara Kauffmann, and the artist Käthe Wilczynski. Later letters refer to at least three further addresses for Grete Ring in the period up to 1945. How she found this accommodation remains unknown.

During the early war years Ring maintained her correspondence with the art historian and former museum director Max J. Friedländer. It was he who had initially recommended her for the job at Cassirer in Berlin – from 1939 he himself was in exile in Amsterdam. From their letters we see how Ring helped Friedländer prepare his book manuscript “Von Kunst und Kennerschaft” for publication. It appeared in English in 1942, as “On Art and Connoisseurship”. The publisher was Bruno Cassirer, the cousin of Paul Cassirer, who had continued his business in exile in Oxford from 1938. Friedländer’s book became a classic of art literature.

Grete Ring was able to take her private collection of drawings with her to England. In the years from 1939, she was even able to build up the collection further, with additional German, French, and also British names. In 1943, Ring learned of Martha Liebermann’s tragic death – confronted with deportation, the 85-year-old had taken her life in Berlin. In memory of her aunt, Ring donated three Liebermann drawings to The Ashmolean Museum in Oxford in 1943: a study of a man in a frock coat and two Dutch landscapes.

Friendships in Exile

The guest book of “Paul Cassirer Limited” shows how Grete Ring quickly established herself on the London art scene. Alongside émigré colleagues, the book contains the names of many renowned British figures, including the art historian Herbert Read or the director of the National Gallery, Kenneth Clark.

Ring’s correspondence from these years provide many further insights into Grete Ring’s new life. She regularly wrote for example to Marianne Feilchenfeldt in Switzerland. Her correspondence with the art historian Julius Held, then in exile in New York, has also been preserved. The artist Katerina Wilczynski was also a close friend during these years. She illustrated numerous greeting cards for Ring from 1938 onwards. Shortly after the end of the war, Ring moved into a new house at 30 South Street, a few hundred metres from her first home on Cleveland Row. Wilczynski’s cards show the front of the building and provide an impression of how Ring lived, how she surrounded herself with her art collection. In 1947, Grete Ring became a British citizen. The post-war period in London according to Marianne Feilchenfeldt, “like the fulfillment of Grete Rings life […] she travelled, she was appreciated everywhere”. When the first signs of a serious illness became apparent in the early 1950s, Ring received get-well wishes from Oskar Kokoschka in the form of a coloured pencil drawing with a handwritten note.

Grete Ring died of leukemia on 18 August 1952. Her heirs were Walter Feilchenfeldt and his wife Marianne. In 1954, Grete Ring’s art collection was donated to The Ashmolean Museum Oxford, where Ring herself had donated works ten years earlier in memory of Martha Liebermann. This room contains a selection of these works, in memory of Ring’s collection.

Showcase

In England Grete Ring continued to publish her art historical research, for example in The Burlington Magazine and in The Art Bulletin. Her only monograph – exploring French painting between 1400 and 1500 – was published by the Phaidon Press in 1949. The publication became the standard work in the field. The book was also simultaneously published in French; a German version did not appear. Ring had already worked on the manuscript during her years in Berlin was later able to collect further materials on research trips in France.

Quotes

With this exhibition project, first steps have been taken to reconstruct the life and work of Grete Ring. Some sources are still undiscovered and many details remain to be deciphered, especially about her activity as an art dealer both before and after her departure from Germany. To conclude our exhibition we present here Grete Ring in the words of her friends. In the film you can follow the trail of Grete Ring in contemporary London.

“Truly irresistible […], admired by all, if occasionally a little feared, for she shrank from no one and nothing.”

Marianne Feilchenfeldt, close friend of Grete Ring’s

“Grete Ring was an absolutely unusual woman whom I loved like hardly anyone else. She was feared by many for her disarming directness, and one continuously experienced the most incredible stories with her.”

Marianne Feilchenfeldt, Grete Ring’s close friend

“You spend your time buying pictures from people, who don’t want to sell them, and selling them to others, who don’t want to buy them. You didn’t learn that from me”

Heinrich Wölfflin, Grete Ring’s doctoral supervisor

“Greta Ring [sic], the remarkable German woman who has made a unique position for herself among the leading art dealers of the day […].”

Sybil Vincent: For Women of Today, in: The Yorkshire Post, 11. Juni 1928

“Her beautiful house in South Street became […] after the war […] a favourite rendezvous for scholars and intellectuals of every nationality. At her parties in a room full of people, she continued to hold the centre of the stage she had set. This is because she was cleverer and wittier than all with whom she surrounded herself.”

Benedict Nicholson, britischer Kunsthistoriker

“Grete Ring had made it clear to me at what level serious art historical work takes place […]. For the first time I was confronted with thinking on an international level, and I realised […] what Germany had lost when it cast out so many of its most exquisite citizens.”

Klaus Geitel, art critic

“She suddenly became very ill in London […]. We had her here [in Zurich] in the hospital for another day, but then she died unexpectedly of heart failure – for her a relief, for us an irretrievable loss.”

Walter Feilchenfeldt senior, business partner of Grete Ring, to Julius Held

“Dear Feilchen, today is the darkest day […] because poor, good Grete is no longer riding around on her broomstick. It is fatal to me to think that it had to be and that she is now in the ground instead of haunting the old house in London to give me a whisky.”

Oskar Kokoschka to Walter Feilchenfeldt senior

“[H]er collection of 19th century German drawings [was] not only by far the most important in private British ownership, but also the collection of highest quality in the whole of Britain. Through her gift, the comparable public collections […] have become modest testaments to this genre of art.”

Colin J. Bailey, Curator, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford