All for Art! Max Liebermann Between Strategy and Cultural Policy

In our audio guide to Exhibition “All for Art! Max Liebermann Between Strategy and Cultural Policy,” you will discover Max Liebermann from beyond his studio, as a strategic cultural politician.

WELCOME

A warm welcome!

Join us today as we follow in the footsteps of Max Liebermann. We look at a painter who revolutionized the German art world. With strategic skill and his Berlin quick‑wittedness, he helped modernism achieve its breakthrough.

EARLY SETBACKS REQUIRED PERSEVERANCE

At the beginning of his career, Liebermann had to fight to be recognized as an artist. Although he was already exhibiting at the Salon in Paris, he still undertook long painting journeys in pursuit of potential commissions.

WALTER LEISTIKOW

The founding of the “Vereinigung der XI” (Association of the XI) was a public scandal – an uprising against rigid academic notions of art and against the Kaiser. Why did the group call itself the “Association of the Eleven”?

THE AIMS OF THE BERLIN SECESSION

Shortly before the founding of the Berlin Secession, the following prophecy was ventured: “Liebermann has suddenly achieved such recognition that one might almost fear that he, who must stand alone, could found a school, could gain influence. That would be a pity. Liebermann is a phenomenon unto himself, difficult to categorize, appealing with his brilliant qualities along with his weaknesses. He stands entirely on his own and can only be appreciated as such.”

THE AIMS OF THE ACADEMY PRESIDENT

Despite his success and his high offices, Max Liebermann remained skeptical of public fuss.

“ART IS CARE AND MUCH WORK”

Throughout his life, Liebermann maintained close contacts with art dealers, museum directors, and art writers. He was also closely connected with the art critic and literary historian Julius Elias, who showed great enthusiasm for Impressionism in Germany.

ENGLISH WALL TEXTS

All for Art! Max Liebermann between Strategy and Cultural Policy

HALL

The exhibition presents the artist Max Liebermann (1847–1935) for the first time as a cultural policymaker. As a pioneer of modernism, he advocated for artistic freedom in the German Empire and the Weimar Republic far more, and far more vehemently, than other actors of his time. It was far from Max Liebermann’s nature to focus solely on his artistic practice. Yet under what conditions was he able to develop into one of the most influential cultural‑political decision‑makers of his era?

Very early on, he began forging contacts abroad and, thanks to these connections, secured participation in international exhibitions, drew the attention of buyers, and caused a stir with at times controversial artistic contributions. His success story, however, was anything but a given: a look back shows that he had to work very actively to achieve his later renown and accept numerous setbacks along the way. Today, Max Liebermann is regarded as one of the most formative artists of his time. As president of the Berlin Secession as well as of the Academy of Arts, he always acted with clear goals, strategically, and at the same time in highly contradictory ways.

The exhibition tells a complex story of power structures, resistance, and at times irreconcilable ideals and aims within the art world. In every room, alongside artworks and photographs, editorial notes can be found that invite visitors to delve into aspects of his career and into decisions that shaped his path.

CABINET TEXT 1

…As one of the most successful artists of his time, Max Liebermann entered the history books. On the occasion of his 80th birthday in the summer of 1927, three exhibitions were dedicated to him. Not only did the Academy of Arts comprehensively honor his oeuvre with a selection of one hundred of his works, the publisher and art dealer Bruno Cassirer also showed pastels, and even at his cousin Paul Cassirer’s gallery, Liebermann’s drawings could be admired. Liebermann had already become an icon of his era during his lifetime. Thus, as early as 1927, it was prophesied: “The overall impression [of the Academy exhibition] is one that can only be experienced in the life’s work of a master who will belong to the history of art.”

The journal Kunst und Künstler (Art and Artist) published a special issue in Liebermann’s honor entitled Im Urteil Europas (In Europe’s Judgment). The most important figures of the time contributed, among them the Minister of Culture Carl Heinrich Becker, Albert Einstein, Thomas and Heinrich Mann, Olaf Gulbransson, Ernst Barlach, Heinrich Wölfflin, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, and many more. Liebermann was not only awarded the Prussian State Medal; even the famous Universum‑Film AG (UFA) came to visit him at Wannsee.

NEW PATHS IN BERLIN 1884–1899

OBJECT TEXT 1

…When Max Liebermann returned to Berlin in 1884, his naturalistic‑looking painting found no recognition within the official art establishment of the German Empire. The following year, Liebermann succeeded in convincing the painter Anton von Werner of his abilities, so that he admitted him to the Verein Berliner Künstler (Association of Berlin Artists) – indispensable for participating in the Academy’s exhibitions.

In 1892, things began to move. In order to distinguish themselves from the mediocrity of the Academy exhibitions and finally give space to modern tendencies, the Vereinigung der XI (Association of the Eleven) was founded in 1892. Together with Walter Leistikow (1865–1908), photographed here in his studio, and others, Liebermann organized his first independent exhibitions at the Kunstsalon Eduard Schulte, achieving attention beyond the region. Shortly thereafter, he was even invited to take part in founding the Munich Secession. Submitted and even exhibited artworks shook traditional notions of art, making it increasingly clear that a renewal of art within the rigid existing structures was not possible.

Liebermann’s early work Beim Hufschmied (At the Blacksmith’s) from 1874 recalls the painting of Mihály von Munkácsy and the Barbizon School and shows where Liebermann stood artistically in those years. The art dealers Bruno and Paul Cassirer exhibited it in 1900 in Berlin alongside works by Giovanni Segantini, Camille Pissarro, Gotthardt Kuehl, and Fritz von Uhde.

OBJECT TEXT 2

…The Munich years, 1878 to 1884, were decisive for Liebermann’s further development. In 1878 he met there the Lübeck genre and history painter Johann Gotthardt Kuehl (1850–1915), who was in close exchange with Wilhelm Leibl. One year later, Kuehl moved to Paris and immersed himself in the art of Édouard Manet and Jules Bastien‑Lepage. At the Paris Salon of 1882, Kuehl, who in France internationalized the spelling of his surname, saw Liebermann’s Freistunde im Amsterdamer Waisenhaus (Free Period in the Amsterdam Orphanage, 1882), which was also shown later in 1899 at the Berlin Secession. The work left a lasting impression on the Lübeck painter, so that he himself took up the motif. Like Liebermann, Kuehl repeatedly travelled to the Netherlands, and they met again in Dordrecht and Katwijk.

In 1889, Kuehl, Liebermann, and the graphic artist and painter Karl Köpping were responsible for the unofficial German participation in the Paris World’s Fair. Because the fair celebrated the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution, the German Kaiser had issued a ban on participation. Together, the three artists nevertheless found a way to assemble German art in France. Kuehl became a member of the Société Nationale des Beaux‑Arts in Paris – one of Europe’s first Secession movements, founded in late 1890 – as did Max Liebermann and Fritz von Uhde.

In 1899, Kuehl, now a professor at the Dresden Academy and recipient of the gold medal, travelled to Berlin for the opening of the first exhibition of the Berlin Secession. There he was represented with a rural interior scene similar to the man reading here. The card‑playing and pipe‑smoking Chaisenträger (Chaise Carriers) after work are also iconic for his oeuvre. The figures depicted performed hard labor, carrying finely dressed ladies and gentlemen in narrow sedan chairs known as chaises.

OBJECT TEXT 3

…With the founding of the Berlin Secession in 1899 and Max Liebermann’s presidency until January 1911, the art scene in imperial Berlin changed profoundly. The artists of the Secession wished for “not an indulgent, but an insightful public.” One hundred twenty‑seven years later, their courage, modernity, and progressiveness still astonish us. The new movement positioned itself against the Kaiser, against the Academy’s feudal dependencies, and against long‑dominant ideals and norms. From the very beginning, the Secession admitted women into its ranks, distinguishing itself clearly from the Verein Berliner Künstler (Association of Berlin Artists) and other Secession movements. Membership in the Berlin Secession required significant concessions and prohibited dual participation in other Berlin exhibitions.

Gustava Iselin‑Haeger (1878–1962) was one of the 108 women within the Berlin Secession. Supported by her father from the outset, she was an excellent draughtswoman. Liebermann was grateful that she “fortunately did not go along with the follies of the Expressionists.” In 1901 she returned from Munich to Berlin and rented a studio in the Künstlerhaus Siegmundshof. She taught at least fourteen female students, among them the daughter of Wilhelm Bode, Marie, and Max Liebermann’s daughter, Käthe.

At the Berlin Secession she mostly exhibited drawings, beginning in 1901. These two works shown here, the summery garden scene and the self‑portrait in the studio, were once presented by Haeger at the Secession. They are not listed in the catalogue, but Secession labels can be found on the reverse of the canvases.

In 1907, her marriage to the Swiss surgeon Hans Iselin led to her departure from Germany for Switzerland, to Basel. As a result, her involvement in the Secession ended very soon thereafter, and her name faded from memory in Berlin.

OBJECT TEXT 4

…At the Secession exhibitions, Liebermann also purchased art himself, for example, in autumn 1909, August Gaul’s (1869–1921) Fischotter (Fish Otter). With this bronze he surprised his wife Martha Liebermann at Christmas. Max Liebermann determined the ideal location for the fountain together with his friend Alfred Lichtwark, using a life‑size model. Today, the fish otter, cast anew in 1997, overlooks the artist’s garden.

Liebermann may have been inspired by his neighbor, the art collector Eduard Arnhold, in whose expansive garden a life‑size lioness by Gaul had stood since 1901. The Oppenheim couple also maintained contact with the sculptor, and a penguin fountain was placed in their Wannsee garden as well. Emil Orlik portrayed August Gaul while he was modeling this fish otter in his studio. When Gaul came to Berlin, he had won an annual pass to the Berlin Zoological Garden in a lottery. Later, as a master student of Reinhold Begas, the most successful German sculptor of the time, and with an exclusive contract with the art dealer Paul Cassirer, Gaul was, from 1898 onward, free in his artistic practice and his focus on animal sculpture. He, too, participated in the founding of the Berlin Secession and exhibited there from the very beginning.

PARENTS’ DRESSING ROOM

EARLY CONTACTS 1866–1880

OBJECT TEXT 5

…Even as a schoolboy in Berlin, Max Liebermann devoted himself to art. During his years at the Gymnasium, he attended drawing lessons twice a week with the famous painter of horses Carl Steffeck (1818–1890). After completing his Abitur in 1866 at the Friedrich‑Werdersches Gymnasium, he began studying chemistry at the Faculty of Philosophy at the University of Berlin. However, because he failed to attend lectures, he was expelled for “lack of diligence in his studies.” In 1868, Liebermann began studying at the Grand Ducal Saxon Art School in Weimar, first with the illustrator Paul Thumann and the Belgian history painter Ferdinand Pauwels.

A decisive impulse came in 1871 with his encounter in Düsseldorf with the Hungarian painter Mihály von Munkácsy (1844–1900). Munkácsy’s bold socialist realism and his depictions of working people inspired Liebermann. A studio scene by Munkácsy is shown here opposite a view into Liebermann’s studio. When the Hungarian painter later came to Weimar, he praised the young artist for his depiction. Liebermann was also moved by his visit in 1873 to the famous Viennese salon painter Hans Makart, remarking that he wished to have “as much talent as he.”

From late 1873 onward, Liebermann lived in Paris, then the pulsating metropolis of art. After the Franco‑Prussian War of 1870/71, however, he found it difficult as a German to gain access to the Parisian art scene. Artistically, he drew wide‑ranging inspiration from the Barbizon School and the work of Jean‑François Millet.

OBJECT TEXT 6

…From the mid‑1870s onward, Liebermann travelled regularly to Holland. An important contact became the painter and graphic artist Jozef Israëls (1824–1911), whom he met there in 1876. A close friendship developed over the years, and in 1884, Israëls even accompanied the Liebermanns for part of their honeymoon.

In places such as Laren, and in exchange with painters of the Hague School such as Anton Mauve, Liebermann found his central pictorial motifs. Here he initially focused on depicting the working population. While he was still struggling for recognition in Berlin, he celebrated great success at the Paris Salon with these Dutch subjects, such as Altmännerhaus (The Old Men’s Home) from 1881, and received his first awards.

How deeply Israëls and Liebermann inspired one another artistically is illustrated by the two depictions of women in the exhibition: an older woman warming herself by the fire and a younger woman absorbed in her needlework. Though differing in age and technique, they resemble each other in conception. Liebermann admired Israëls for his artistic achievement; later, the Dutchman became a corresponding member of the Berlin Secession and, from 1902 onward, even an honorary member.

Israëls is said to have once asked Liebermann to write about him. How difficult this was for him – reporting objectively on a cherished friend – is revealed in the following lines: “Only a lyrical poet could do full justice to Israëls, for Israëls’s painting is a poem become color; a simple folk song, childlike, simple in the biblical sense; all heart, all feeling […] He is in Holland what Menzel was for us […] Thus one bather points him out to another when the small old gentleman strolls along the beach of Scheveningen […] Israëls created the modern Dutch school.”

OBJECT TEXT 7

…At Carl Steffeck’s studio, Max Liebermann met the painter Thomas Herbst (1848–1915), who was the same age, and they became friends. From 1869 onward, they studied together in Weimar and inspired one another from that point on. Liebermann’s famous and sensational work Die Gänserupferinnen (The Goose Pluckers, 1871/72) is based on a preparatory drawing by Thomas Herbst. Between 1873 and 1878, Liebermann lived in Paris, Herbst in Düsseldorf, and in 1877, Herbst followed him there. They shared a studio on the Boulevard de Clichy and undertook joint painting trips to Holland.

The watercolor by Herbst reproduced here (1877), now considered lost, shows Max Liebermann in front of his work Klatschgeschichten (Gossip Stories) in the Paris studio. He had submitted Klatschgeschichten to the Paris Salon, but it was not accepted. Therefore, he made the drastic decision to cut it down. Today, only the mother with child from the painting is known, and it is preserved at the Kunstmuseum Winterthur.

Later, in Munich, Herbst and Liebermann met again. Herbst returned to his native city of Hamburg in 1884 and Liebermann to Berlin. Liebermann visited Herbst repeatedly in Hamburg, whereas only a few return visits to Berlin are known. Liebermann placed great value on the judgment of his artist friend, for example when selecting works for exhibitions. How great an influence Herbst exerted on Liebermann is described in a letter he wrote in 1909 to Alfred Lichtwark: “[…] for my artistic training I owe more than to any other colleague of my generation to the influence of my friend Thomas Herbst.”

CABINET TEXT 2

…From its founding in 1899 until 1913, the Berlin Secession held annual exhibitions accompanied by a catalogue. All catalogues shown here come from the estate of the painter Gustava Iselin‑Haeger. The catalogues enjoyed great popularity, with their supplementary illustrations, and appeared in several editions. Additional financial support was secured through advertisements placed by art dealers and industrialists. With the first exhibition, the Secession sent a clear signal. To pre‑empt potential criticism, the organizers gathered primarily German artists such as Max Liebermann, Max Slevogt, Lovis Corinth, Wilhelm Leibl, Adolph von Menzel, Hans von Thoma, Wilhelm Trübner, Carl Vinnen, and women artists such as Ilse Hai, Dora Hitz, Käthe Kollwitz, Sabine Lepsius, Ernestine Schultze‑Naumburg, and Julie Wolfthorn.

From the outset, space was provided for paintings, sculptures, and prints. To expand the market for modern art, an additional black‑and‑white exhibition devoted exclusively to graphic art was launched in the winter of 1901/02. Liebermann played a decisive role in establishing the Berlin Secession internationally. From 1900 onward, artists such as Giovanni Segantini, Anders Zorn, Auguste Rodin, Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and James Abbott McNeill Whistler were represented and attracted considerable attention. The exhibitions of the Berlin Secession lasted roughly five months in the summer and two months in the winter. The catalogues and admission tickets were designed by the board and, in the early years, printed at the publishing house of Bruno and Paul Cassirer, and later only by Paul Cassirer.

DAUGHTER’S BEDROOM

THE INTERNATIONAL BERLIN SECESSION 1900–1911

OBJECT TEXT 8

…Since November 1897, Max Liebermann and the Belgian sculptor Constantin Meunier (1831–1905) had known one another personally. Together with him, Liebermann was elected to the Academy in 1898, after this recognition had been denied to him for more than ten years.

Max Liebermann drew the sculptor shortly after their first meeting and apparently misunderstood the friendly interaction, for he sold the drawing, successful in his own eyes, to the Municipal Museum of Magdeburg for 1,500 marks. When Meunier learned of this, he was offended by the sale of the friendship portrait, so Liebermann, in order to smooth things over, asked the museum to return the work and attempted to reverse the purchase. In exchange, he offered the museum a pastel portrait of Gerhart Hauptmann and, in addition, a small portrait of Theodor Fontane.

In 1900, Meunier was represented at the Berlin Secession with no fewer than ten works, including a plaster figure of a porter. Meunier made a name for himself as a sculptor and achieved exhibition successes with his depictions of physically strenuous labor. He developed a particular approach to the motif of the working class, emphasizing their strength and giving them a dignified expression.

OBJECT TEXT 9

…Together with Hugo von Tschudi, the progressive director of the Nationalgalerie, Liebermann visited the French sculptor Auguste Rodin (1840–1917) in June 1896 in his studio in Meudon, southwest of Paris. After several letters, Liebermann succeeded in convincing Rodin to participate in the Berlin Secession. Already in 1900, he was elected a corresponding member, and from 1901 onward he was listed as an honorary member.

That Rodin’s Büste von Jules Dalou (Bust of Jules Dalou, 1896) would one day be displayed in the painter’s summer house at Wannsee would likely have pleased Max Liebermann. For the painter was a great admirer of Rodin and donated precisely this bust, exhibited here, to the Berlin Nationalgalerie in autumn 1896. With this carefully considered gift, Liebermann secured lasting appreciation for the sculptor in Berlin, an appreciation that continues to this day. The modeled Jules Dalou was a sculptor friend of Rodin’s; he had exhibited at the Paris Salon but, due to his political proximity to the Paris Commune of 1871, had to flee to England. He was later able to return to France and, from 1890 onward, exhibited at the Société Nationale des Beaux‑Arts, as Liebermann would later do as well.

Liebermann had planned to acquire a cast of Ehernen Zeitalters (The Age of Iron, 1876/77) for his Wannsee garden and corresponded with Rodin about it. Although they had even agreed on a price of 7,000 francs, the purchase did not succeed. Liebermann wrote in despair: “Unfortunately Rodin still does not send the figure, as he says because of the patina, though I assume out of dawdling: in any case I cannot get it out of him. He writes wonderful letters of the greatest kindness, but I would rather have the figure.”

OBJECT TEXT 10

…Liebermann also presented a wide variety of his own works at the Secession, usually his newest motifs, among them, in 1899, a Schulgang in Laren (School Corridor in Laren), similar to the study exhibited here. Already at the Second Exhibition of the Berlin Secession, foreign artists were represented in great diversity. Its chairman, Max Liebermann, worked tirelessly for the success of the Secession and even undertook personal visits to persuade individual artists to participate in Berlin.

In the 1890s, Liebermann had met the Swedish painter Anders Zorn (1860–1920). In these years, Zorn, who had already been awarded the gold medal at the Paris World’s Fair, was seeking to establish connections within the German art scene. Zorn had been a corresponding member of the Secession in Munich since 1893 and in Vienna since 1897. In Berlin he participated in 1900 with four works, including a portrait of a lady named Maja von Heijne, which Liebermann described as “one of the most beautiful he has made.” The portrait in question can be found in the neighboring room in the vitrine of Secession catalogues. Zorn also portrayed Liebermann, including in the etching shown here. Liebermann invited Zorn to Berlin as well, to paint his wife, Martha Liebermann.

In the 1900 catalogue, the Second Exhibition of the Berlin Secession, one already finds Ferdinand Hodler, Hans von Marées, Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Auguste Renoir, Giovanni Segantini, and James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Among the sculptors were Constantin Meunier and Auguste Rodin, who brought international ideas to Berlin. In the third year, Vincent van Gogh, Jozef and Isaac Israëls, Constantin Somoff, Henri Toulouse‑Lautrec, and Jan Veth joined them. In 1903, Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Édouard Manet, and many others followed. The jury’s selection of works provoked fierce criticism almost from the beginning, which intensified markedly in 1903 and 1904. The Secession was criticized for “not having become a place where every artistic direction could express itself equally. Through an excessive emphasis on art of a particular direction and through an excessive inclusion of foreign works, it has not sufficiently promoted the interests of its regular members and of German art.” In fact, the Berlin Secession had intended to oppose elitist claims, yet it fell into familiar patterns and did not always make comprehensible decisions about whom it admitted into its ranks. The criticism of the Secession’s board escalated to such an extent that Liebermann resigned his long‑held position as chairman in early 1911.

CABINET TEXT 3

…Energetic journalism accompanied the events of the art world. Around 1900, caricature art experienced a heyday in the German Empire. Artistic personalities and new stylistic tendencies were extensively commented on and illustrated in satirical magazines such as Ulk (Josh), Lustige Blätter (Funny Newspaper), Simplicissimus, and Kladderadatsch (Scandal).

A popular topic was the founding of the Berlin Secession and its exhibitions under Liebermann’s leadership. As co‑founder and chairman, he was regarded as a symbolic figure of an artistic opposition to the official conservative art establishment. In caricatures he appeared first as chairman of the Secession and later as president of the Prussian Academy of Arts. Some drawings were charged with antisemitism, presented a distorted picture of reality, and fueled prejudice. Caricatures hostile to modernism were published that went far beyond the person of Liebermann. The Secession was accused of being too Francophile, arrogant, unable to tolerate criticism, and interested only in power and money.

Not only these publicly fought disputes over art, but also the shifting political circumstances brought a rupture to this vibrant artistic scene. With the outbreak of the First World War, the artistic community became further divided: some had been swept up in the war enthusiasm, while others returned disillusioned and expressed pacifist views. After the war, artists, writers, and intellectuals processed the trauma in diverse ways in their works and paved the way for anti‑war movements. A new era began.

DAUGHTER’S SALON

THE ACADEMY 1920–1932

OBJECT TEXT 11

…The modern artist Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945) chose subjects that had previously received little attention: today, one associates with her powerful, admonishing scenes. Gerhart Hauptmann’s 1893 premiere of Die Weber (The Weavers) inspired Käthe Kollwitz to create the graphic cycle Der Weberaufstand (The Weavers’ Revolt). She worked on it for over five years and completed an impressive visual synthesis in 1898. It aroused public interest at the Great Berlin Art Exhibition, and Max Liebermann recommended her for a gold medal, but Kaiser Wilhelm II did not follow his suggestion.

Since the founding of the Secession, Käthe Kollwitz had been represented there, but she did not become a corresponding member until 1901. She was also a member of the German Artists’ Association, founded in 1903. To what extent Liebermann, as a board member, contributed to her receiving the Villa Romana Prize in 1907 has not yet been clarified. Contradictions also characterize Käthe Kollwitz’s actions: in 1911, she signed Carl Vinnen’s German‑national Protest by German Artists, out of incomprehension for the appreciation shown to the Expressionist Henri Matisse. A few weeks later she revoked her approval. She also participated in the Jury‑Free Art Exhibitions, which opposed the Berlin Secession, but withdrew from them under pressure from Liebermann. When Liebermann resigned from his position in the Secession, she became part of the board in 1912.

In 1919, she became the first female member of the Academy since 1833 and was simultaneously appointed professor. Käthe Kollwitz served on the exhibition commission and consulted with Max Liebermann regarding submitted works. From 1928 onward, she headed a master studio for graphic art and, like Liebermann, was awarded the Order Pour le Mérite for Sciences and Arts, as one of the few women of her time. On February 15, 1933, Käthe Kollwitz was forced to resign from the Academy because she supported an appeal to form a united front against National Socialism.

OBJECT TEXT 12

…Max Liebermann and George Grosz (1893–1959) could not have been more different: on the one hand the liberal, upper‑middle‑class painter; on the other the artistically radical graphic artist inclined toward communism. Nevertheless, in 1924 Liebermann, as president of the Academy, advocated vehemently for Grosz when he was charged for his portfolio Ecce Homo and for the dissemination of immorality.

Liebermann appeared in court as an expert witness. Although Grosz’s drastic aesthetic was personally foreign to him, he defended the principle of artistic freedom. Art, he argued, stood “beyond morality and immorality.” Through this intervention, Liebermann prevented the work from being classified as outright obscenity; despite this, Grosz was sentenced to a fine and the printing plates had to be destroyed.

In the Grosz case, Liebermann demonstrated greatness: he defended the freedom of art independently of his own artistic convictions and protected others regardless of their political stance, guided by the conviction that art should be autonomous.

OBJECT TEXT 13

…Max Liebermann was in close exchange with the draughtsman, graphic artist, and photographer Heinrich Zille (1858–1929), so he could be certain of receiving a congratulatory note for his 80th birthday. Liebermann supported the chronicler of the Berlin Milljöh (milieu) invited him to the Secession in 1901, and in 1924, paved his way into the Academy of Arts as well as to the title of professor. Life models in his studio inspired Zille’s lithograph Modellpause (Model Break). When he was charged in 1925 with the “dissemination of obscene materials,” Liebermann sought prominent support for him, including Max Slevogt and Alfred Kubin. Thanks to this intervention, the case was dismissed. The court withdrew with the reasoning that although “objective indecency” was present, the artist was “subjectively” unaware of it. Liebermann thus used his authority as Academy president to safeguard artistic freedom and, when necessary, even opposed the judiciary. Although Max Liebermann advocated openness in his office, he deliberately excluded personal adversaries. He denied exhibition opportunities by all means to artists with whom he was in conflict, such as Emil Nolde or Eugen Spiro. His tolerance ended with Expressionism.

OBJECT TEXT 14

…Oskar Kokoschka (1886–1980) was one of the few who raised his voice in 1933 when Max Liebermann was pressured to resign from the Academy of Arts. Kokoschka was still living in exile in Paris at the time, before he had to flee to Prague.

His letter Die fehlende Stimme. Für Max Liebermann (The Missing Voice. For Max Liebermann), which he published in the Frankfurter Zeitung, can be understood as a passionate act of restitution. He emphasizes the Liebermann family tradition; their role as pioneers and innovators, as well as Max Liebermann’s achievements of light and freedom in painting. He elaborates on the painter’s attitude toward art and truth, describes the tragic resignation from the Academy, criticizes contemporaries for their lack of solidarity, and ends with a courageous appeal to the artistic community.

Liebermann held Kokoschka in high esteem; in 1931 he remarked, “Among the artists who now stand in the middle of their lives, Kokoschka is unquestionably one of the most gifted. From Klimt, he has become thoroughly familiar with craftsmanship, which is no small thing and something only few possess, and already at his first Berlin exhibition at Paul Cassirer’s he presented excellent work, especially in portraiture. […] Kokoschka is a born painter.”

Liebermann responded to the open letter: “Kokoschka’s letter in the Frankfurter Zeitung is as courageous as it is principled, and I would gladly thank him if I could find out where he is at the moment.” How severely Liebermann’s freedom was already restricted at this time is shown in the following lines: “Unfortunately, writing letters is now forbidden to one, and the secrecy of correspondence as well, especially given the currently tense relationship between Austria and Germany […]”

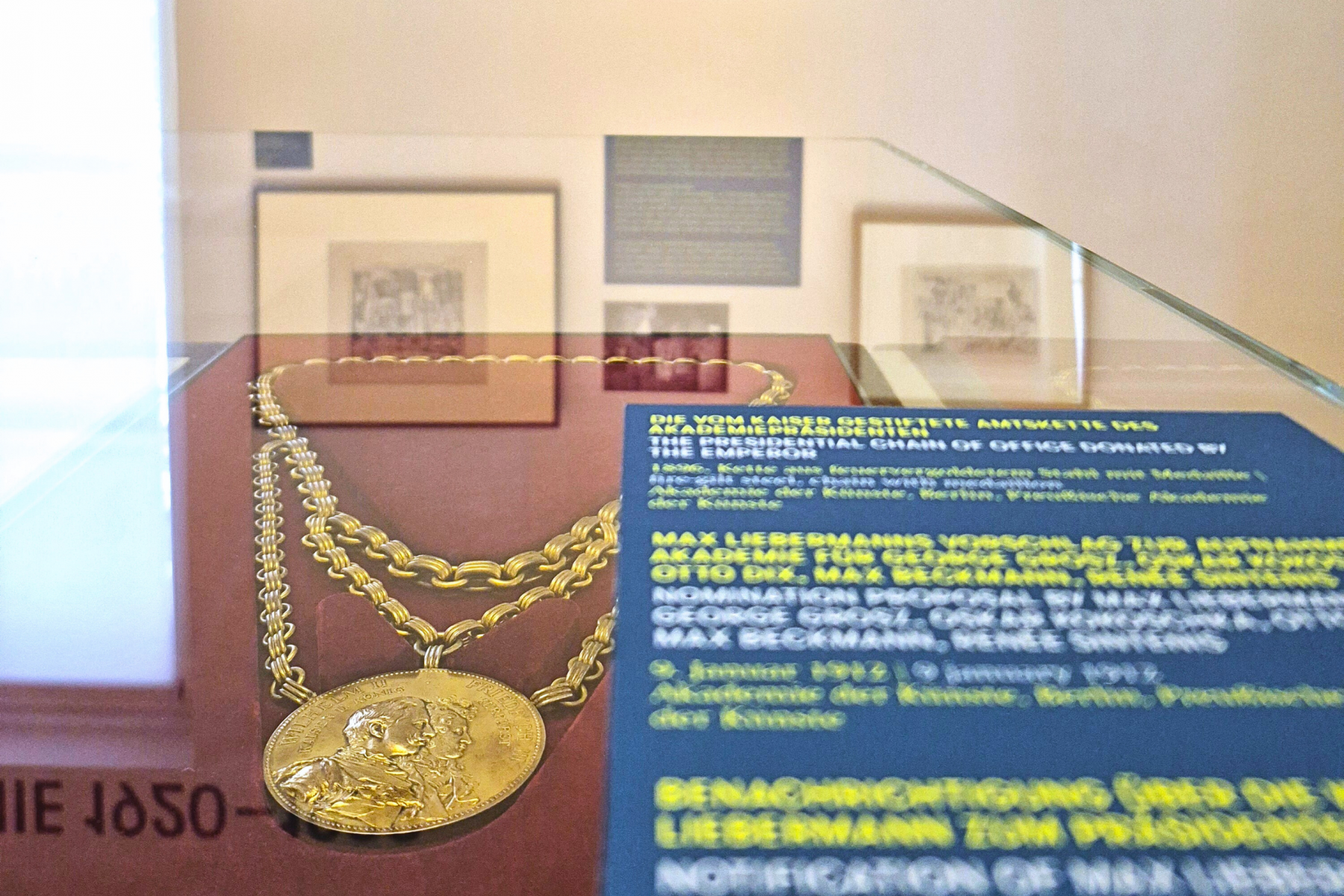

CABINET TEXT 4

…The presidential chain, endowed by Kaiser Wilhelm II on the occasion of the institution’s 200th anniversary in 1896, was reserved for the Academy’s dignitary. With the notification of his election in 1920, Liebermann assumed this honorable office. From 1920 to 1932, Max Liebermann headed the Prussian Academy of Arts. With authority, he led the formerly royal institution into the modernity of the Weimar Republic. His goal was renewal from within: he opened the Academy to women and included younger generations of artists.

The central instrument of his cultural policy was the exhibitions, and he also proposed future members. He strengthened the Academy’s reputation through representative members’ exhibitions in spring and autumn, allowed open submissions, and also presented older artists such as Dürer, Rembrandt, Blechen, Schadow, and Menzel. Austrian art, Chinese art, and ancient American art were also shown, and even Goethe and his world were honored. His opening speeches invoked a liberal ethos that placed quality above stylistic allegiance, although he gave no space to the radical avant‑garde such as Dada. In 1926, the new Section for Dichtkunst (Poetry) was introduced, with Gerhart Hauptmann, Arno Holz, and Heinrich and Thomas Mann as founding members. The Liebermann era ended with the National Socialist seizure of power. In the face of antisemitic hostility, Liebermann resigned his honorary presidency on 7 May 1933, and left the Academy. When the antisemite Max von Schillings assumed the presidency, no Jewish artists were no longer exhibited.

HALLWAY

THE MARKET FOR LIEBERMANN’S PORTRAITURE

OBJECT TEXT 15

…Liebermann maintained his contacts with art dealers such as Fritz Gurlitt, the cousins Bruno and Paul Cassirer, with Théodore Duret in Paris, and with the Colnaghi Gallery in London with great diligence. Equally essential for his reputation was his personal exchange with art critics such as Emil Heilbut and Curt Glaser. In the museums he was well acquainted with Alfred Lichtwark, Max J. Friedländer, Wilhelm Bode, Georg Treu, Max Lehrs, Hugo von Tschudi, and Gustav Pauli.

Around the turn of the century, Liebermann became famous as a portrait painter. Here we find a portrait of Theodor Stoperan (1867–1938), the long‑time secretary of the Berlin Secession, who also supported the Kunstsalon Paul Cassirer from 1910 to 1920. The artist painted him in 1912 and may have oriented himself toward Wilhelm Leibl’s 1876 portrait of Carl Schuch, who also wore such a striking hat. This is quite conceivable, as Liebermann greatly valued Leibl’s portraiture; the Cologne painter had already been represented in the first year of the Berlin Secession with portraits and rural genre scenes.

In 1908, Liebermann painted Bertha Biermann (1840–1930). The work remains in family ownership to this day. Biermann was connected with the Bremen senator and cigarette manufacturer Friedrich Ludwig Biermann, and Liebermann maintained contacts in Bremen through Gustav Pauli, the director of the Kunsthalle there. Apparently, the sitter was very satisfied with the portrait, so much so that she even purchased an important Liebermann work, Die Kuhhirtin (The Cowherdess, 1908), for the Kunsthalle Bremen.

In his portraits, Max Liebermann presented himself as a member of Berlin society, in a suit before the easel. Significant for his commissions was the Gesellschaft der Freunde (Society of Friends), the cultural center of the Jewish community in Berlin. Among its members, alongside the Liebermann family, were the Mendelssohn, Mosse, Rathenau, Reichenheim, and Ullstein families. Bankers and industrialists who collected his works included later neighbors such as Eduard Arnhold, Oscar Huldschinsky, and Hugo Oppenheim.