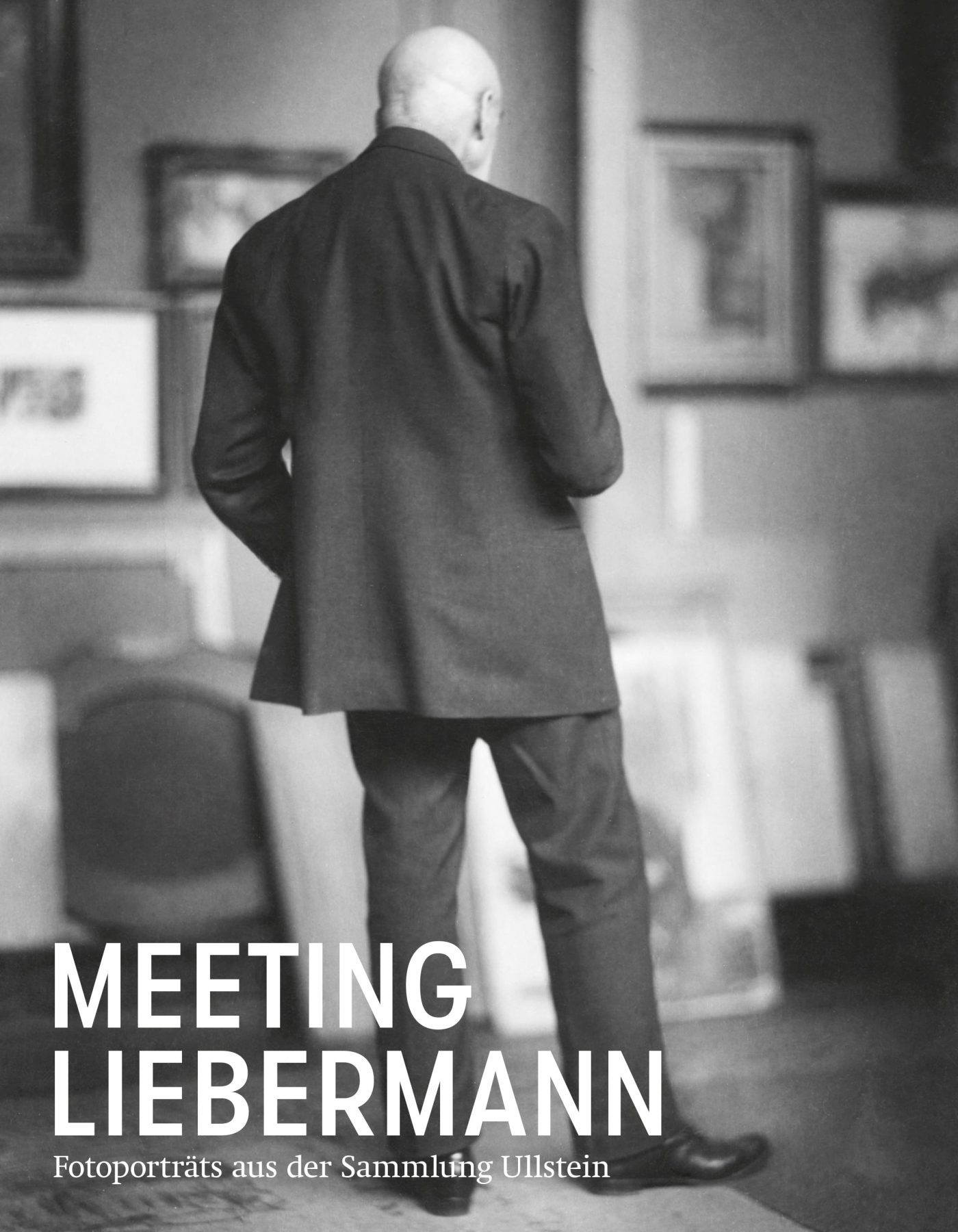

Über die Ausstellung

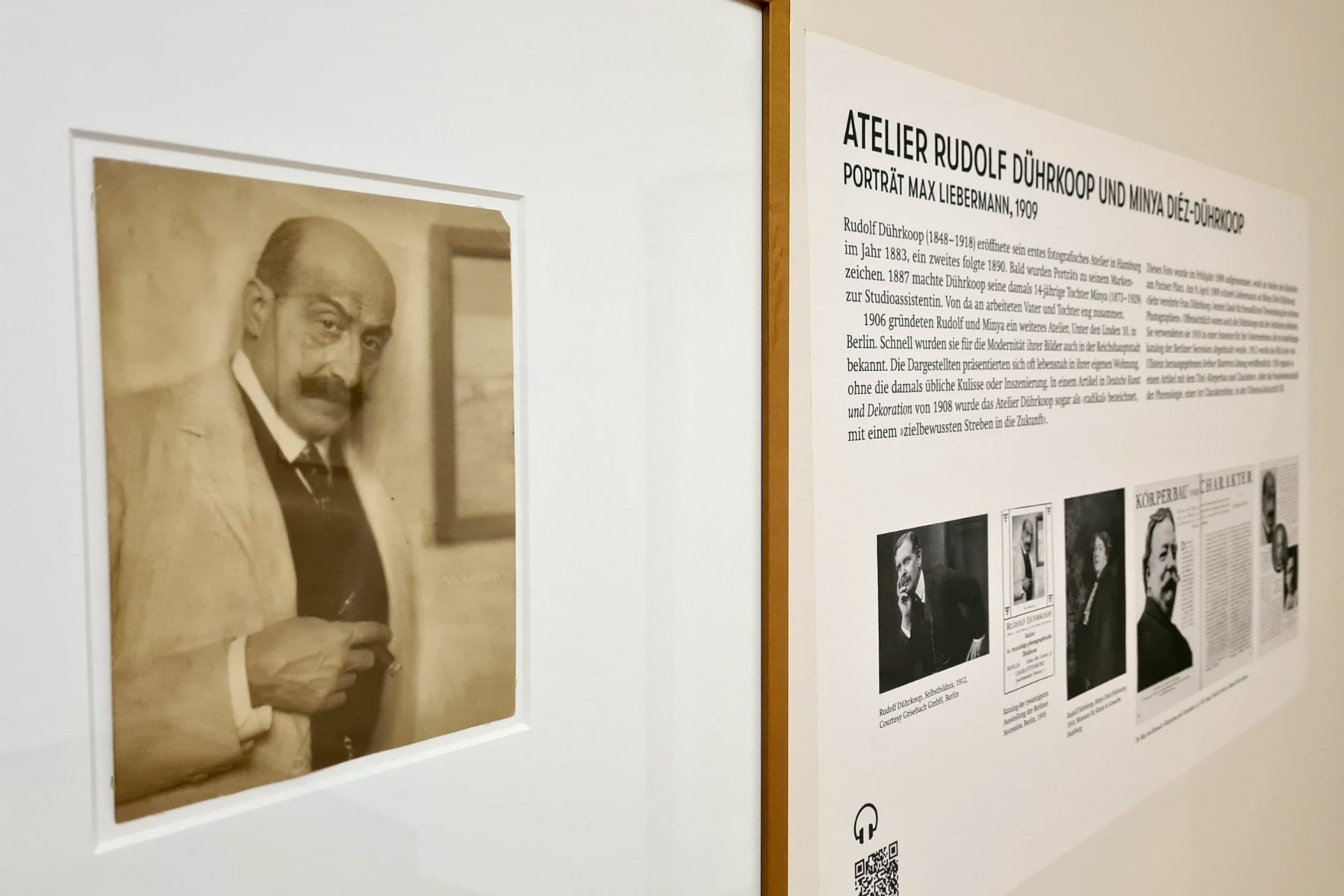

Den Kern der Ausstellung bilden fotohistorisch aufschlussreiche Originalabzüge, u.a. von Yva, Nicola Perscheid, Frieda Riess und Erich Salomon, welche heute in der Sammlung Ullstein bei ullstein bild in Berlin aufbewahrt werden. Sie sind Zeugnisse der vielfältigen Begegnungen Liebermanns mit fünfzehn richtungsweisenden Fotograf*innen in der Zeit von 1905 bis 1932. Die Lichtbildkünstler*innen trafen auf den berühmten Zeitzeugen, welcher sich öffentlichkeitswirksam ausgezeichnet in Szene zu setzen wusste.

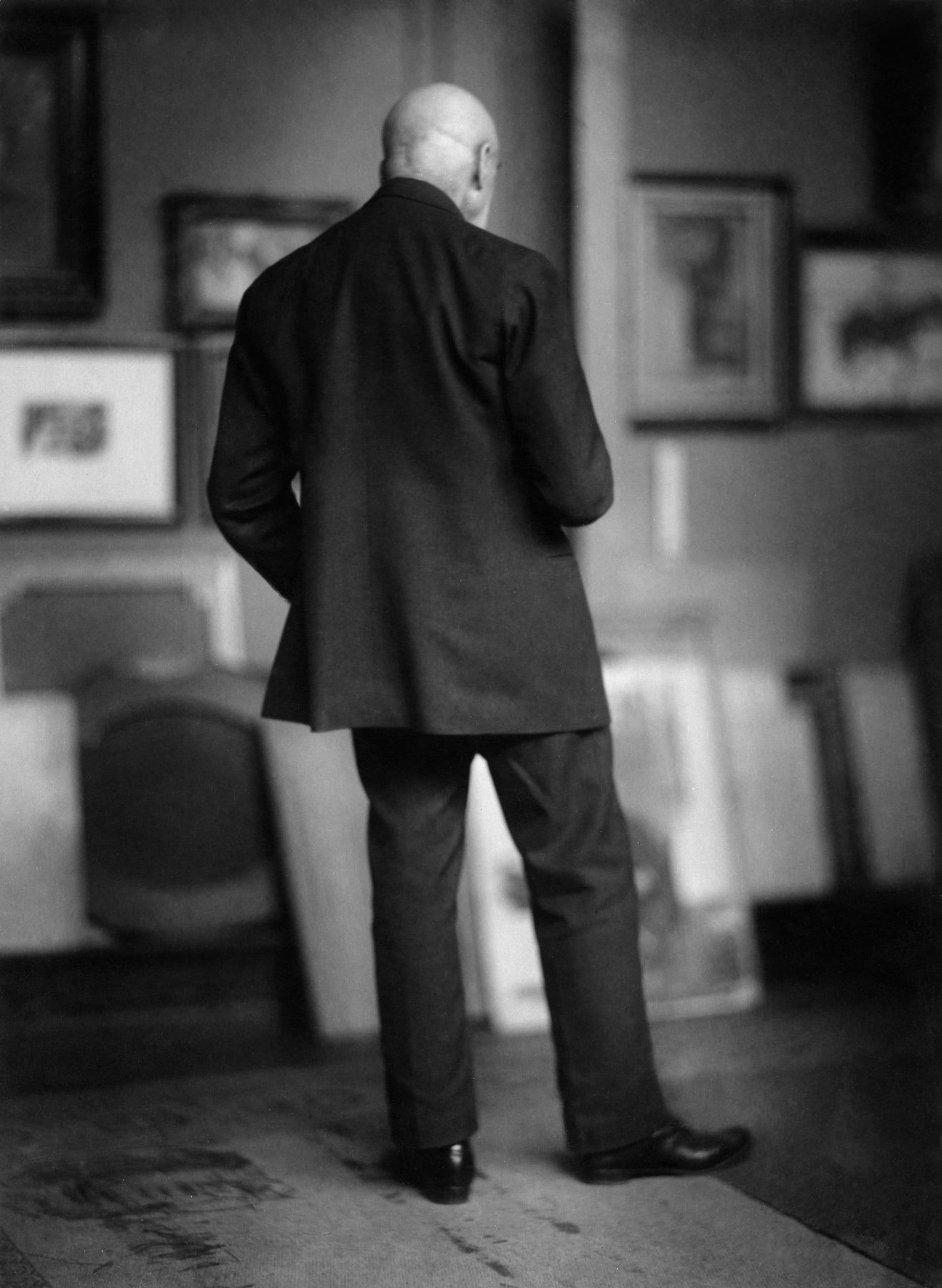

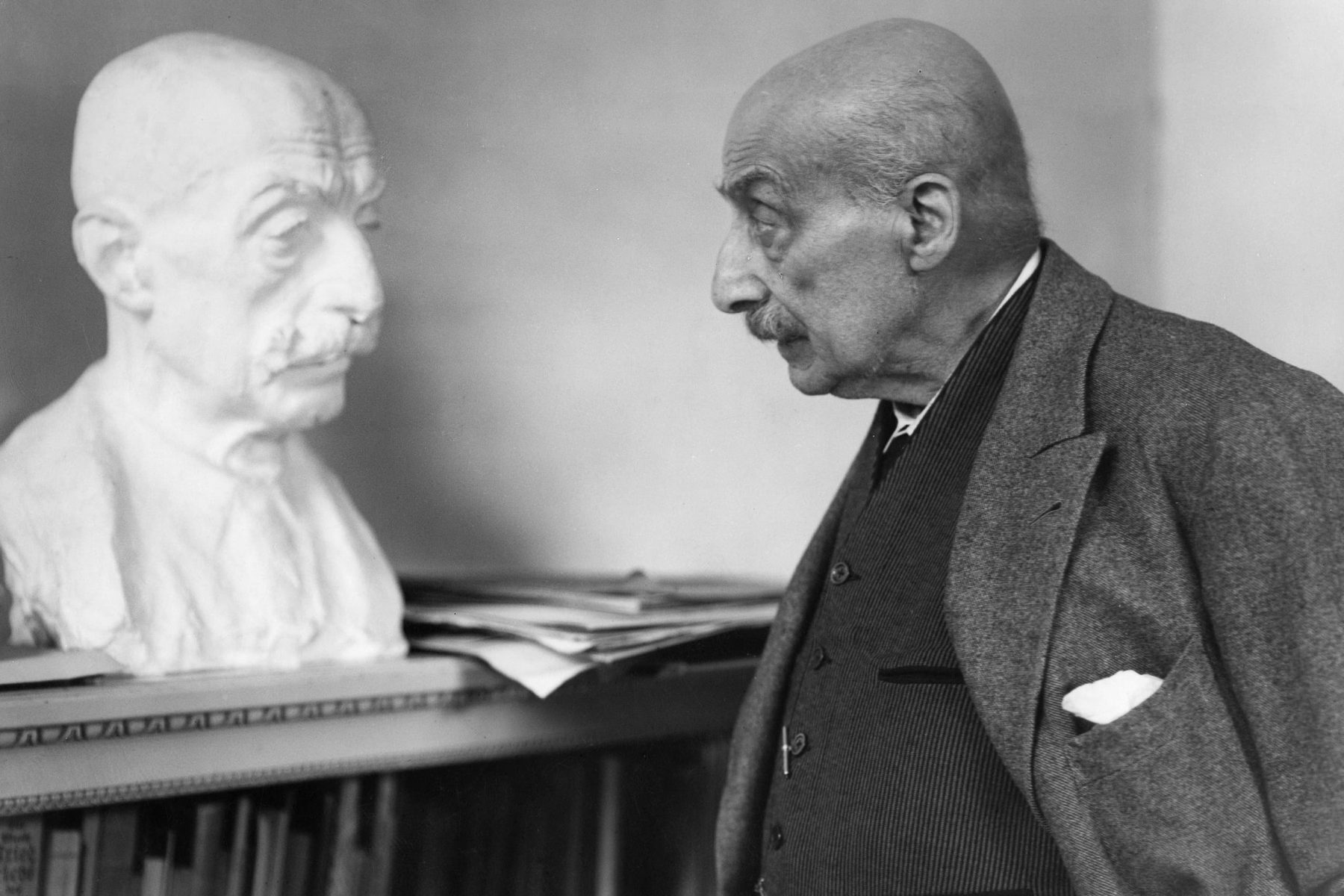

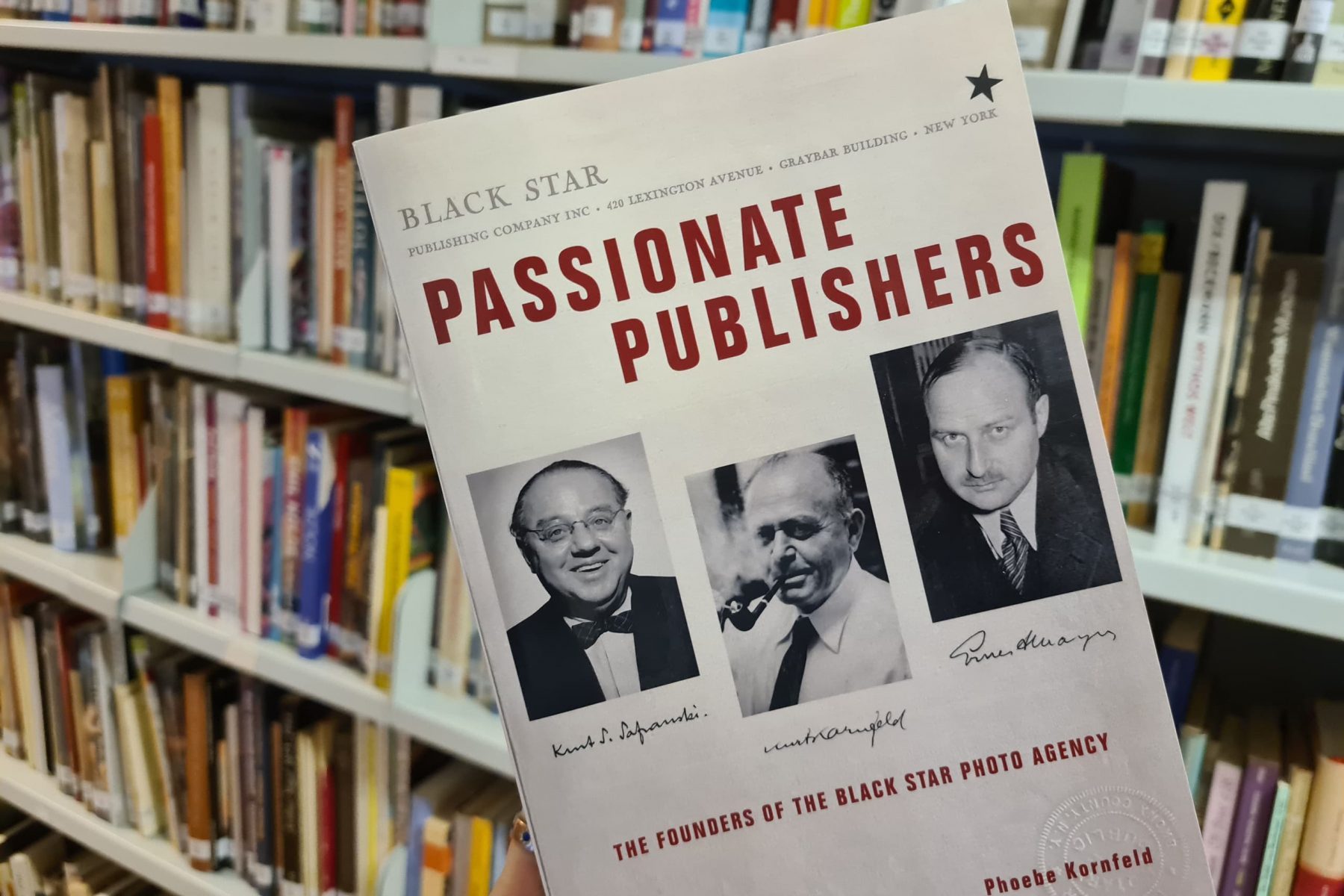

Doch einige ihrer Abbilder zeigen einen ganz anderen Liebermann und überraschen durch ihre Intimität und ihre Direktheit. Wer waren die Künstler*innen, die Max Liebermann ablichten durften? Wie kam es zu den Aufträgen und welche Bedeutung hatten die Fotoporträts des berühmten Max Liebermanns für das berufliche Renommée der Fotografierenden? Wie auch die Geschichte des Ullstein Verlags sind einige der in der Ausstellung präsentierten Biografien eng verbunden mit Verfolgung, Exil, Widerstand und politischer Anpassung.